After transitioning into IT support, I became increasingly interested in the systems that underpin enterprise environments.

Active Directory plays a central role in identity, authentication, and access control, but understanding it at a deeper level requires hands-on experience beyond day-to-day support tasks.

To develop that experience, I built a production-grade Active Directory lab at home - an environment where I can design architectures, test automation, intentionally break things, and rebuild them without risk to production systems.

Rather than treating this as a theoretical exercise, I wanted a homelab that mirrors the kinds of challenges found in real enterprise environments.

The goal wasn’t just to stand up Active Directory and call it “working,” but to use it as a platform for practicing core systems administration skills, including:

- Designing organizational unit and group structures that scale

- Automating user provisioning and lifecycle workflows

- Understanding the real-world impact of Group Policy design

- Testing backup, recovery, and failure scenarios

- Practicing decision-making from a systems administrator’s perspective, not just end-user support

A homelab provides something production environments can’t: the freedom to experiment, make mistakes, and rebuild repeatedly without risk to users or business operations.

That freedom is what turns configuration knowledge into operational understanding.

The Hardware: Keeping It Realistic

Figure: Leveno ThinkCentre Tiny M720q running Windows Server 2022

I’m running this lab on a Lenovo ThinkCentre Tiny M720q, a small form factor PC I picked up used. It’s modest hardware by design, but capable enough to run multiple infrastructure services simultaneously.

Current setup:

- CPU: Intel Core i5

- RAM: 16GB (enough to run multiple VMs comfortably)

- Storage: 512GB SSD

- Hypervisor: Windows Server 2022 with Hyper-V

- Network: Gigabit Ethernet with DHCP reservation

This system isn’t dedicated to a single role. The intent is to host a small but realistic set of core enterprise services - ie. Active Directory, DNS, DHCP, file services, and supporting infrastructure - each running in its own virtual machine where appropriate.

Why Hyper-V?

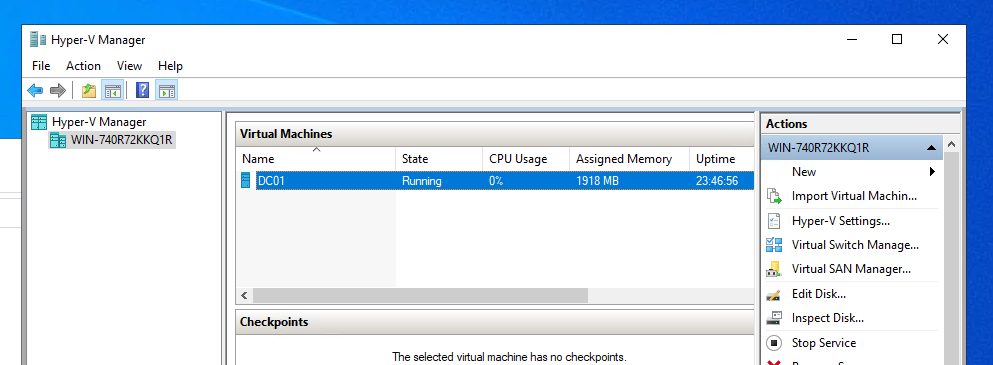

Figure: DC01 running as a VM on Hyper-V

In production environments, core services like domain controllers, file servers, and infrastructure roles are almost always virtualized. Using Hyper-V allows me to mirror that reality while gaining practical experience with:

- VM lifecycle management

- Service isolation and role separation

- Backup, restore, and recovery workflows

- Safe change testing via checkpoints

Snapshots (checkpoints) let me make invasive changes, test failure scenarios, and roll back cleanly - something that simply isn’t possible with physical-only deployments.

This keeps the lab grounded in real-world practices. I’m not optimizing for convenience or shortcuts; I’m building and operating it the way these systems are typically deployed in enterprise environments.

Designing the Active Directory Structure

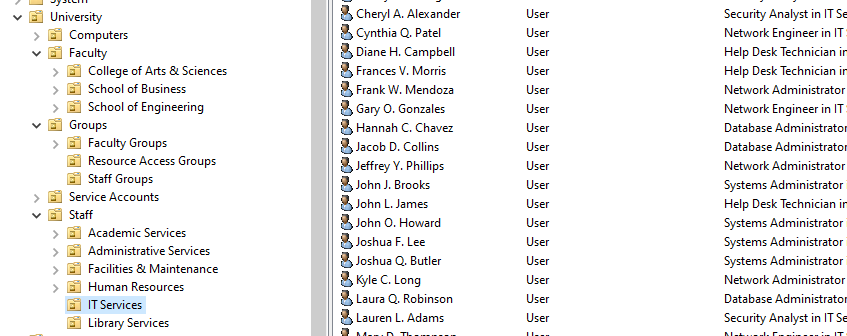

Figure: University Structure in AD

One of the advantages of a homelab is that the organization itself is hypothetical. There’s no production impact, no political baggage, and no legacy constraints - which makes it a surprisingly fun space to think through design decisions and see how they play out.

I chose to model a mid-sized university because it naturally introduces complexity without being contrived. Universities sit in an interesting middle ground: they’re large enough to require structure and delegation, but diverse enough that a single approach doesn’t fit everyone.

The split between staff and faculty alone creates meaningful design challenges. Staff roles tend to be stable, department-driven, and policy-heavy. Faculty roles are more fluid, often spanning departments, research groups, and shared resources. That difference shows up immediately in how accounts, groups, and policies need to be designed.

From there, the model opens the door to realistic scenarios:

- Research staff needing access to specific network shares

- Faculty belonging to multiple departments or projects

- Shared lab computers with different policy requirements

- Administrative staff with strict access controls

- Service accounts supporting departmental applications

To support those scenarios, I built the following Active Directory structure:

University

├── Staff

│ ├── IT Services

│ ├── Human Resources

│ ├── Facilities & Maintenance

│ ├── Library Services

│ ├── Administrative Services

│ └── Academic Services

├── Faculty

│ ├── School of Engineering

│ │ └── Computer Science

│ ├── College of Arts & Sciences

│ │ ├── English Department

│ │ └── Mathematics Department

│ └── School of Business

├── Computers

│ ├── Faculty Workstations

│ ├── Staff Workstations

│ ├── Computer Labs

│ └── Servers

├── Groups

│ ├── Staff Groups

│ ├── Faculty Groups

│ └── Resource Access Groups

└── Service Accounts

The goal here wasn’t to create a “perfect” OU hierarchy, but to give myself a flexible framework that supports real-world ambiguity. The structure is complex enough to force tradeoffs, but simple enough that changes are easy to reason about and test.

Because it’s a lab, I can restructure, refactor, and start over as many times as I want - each iteration sharpening my understanding of how design decisions ripple outward into policy application, group management, and access control.

User Provisioning, Automation, and Recovery Testing

I started by creating a small number of users manually through the Active Directory Users and Computers GUI. That part was intentional. It helped reinforce how objects are structured, how attributes are set, and what the default experience looks like before introducing automation.

Manual creation, however, was never the end goal. Most of the scenarios I wanted to test - scale, failure, recovery - only make sense when users are created and removed in bulk.

Moving to Automation

Figure: AD Bulk Creation Script Running

To simulate realistic environments, I needed a way to rapidly add and remove large numbers of users. I used a CSV-driven PowerShell workflow to populate the directory with hundreds of accounts at once.

The scripts themselves were AI-assisted and adapted to fit the lab, which meant my focus wasn’t on authoring PowerShell from scratch, but on:

- Understanding what the scripts were doing

- Reviewing logic and safety checks

- Adjusting inputs and structure to match my OU and group design

- Observing the impact on Active Directory at scale

That distinction matters in practice: automation is a tool, and knowing how to apply, validate, and safely use it is often more important than writing every line by hand.

The workflow allowed me to:

- Create users in bulk with consistent naming conventions

- Assign department metadata and group memberships

- Populate the directory quickly enough to make failure scenarios meaningful

Why Bulk Operations Matter

Once the directory contained several hundred users, I could test situations that simply don’t come up in small labs.

One example was simulating a serious administrative mistake: an entire department being deleted.

Rather than restoring the full virtual machine, I intentionally approached recovery the way it would typically be handled in a production environment.

Recovery Testing with System State Backups

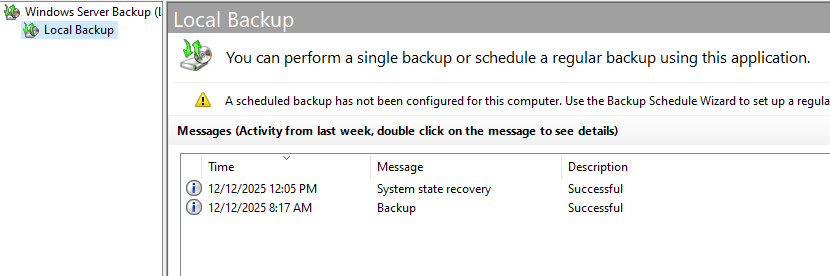

Figure: Windows Server Backup

Before testing failure scenarios, I created regular system state backups using Windows Server Backup. This mirrors how Active Directory is commonly protected in environments with multiple domain controllers, where system state backups are more frequent and practical than full VM restores.

To recover from the simulated deletion, I used Directory Services Restore Mode (DSRM) and performed an authoritative restore of the affected objects from the system state backup. This is the recovery method Active Directory is designed around in multi-DC environments, where replication behavior and object versioning matter.

Working through that process reinforced several important concepts:

- The difference between full server recovery and directory-level recovery

- When authoritative vs. non-authoritative restores are appropriate

- How Active Directory replication interacts with restored objects

- Why backup strategy matters as much as backup existence

More importantly, it gave me a safe place to make destructive mistakes and fully understand the recovery path without impacting real users or systems.

Why This Approach Was Valuable

The combination of:

- Manual GUI work

- Bulk automation

- Intentional failure

- Directory-level recovery

turned Active Directory from something I interacted with passively into something I could reason about operationally.

This wasn’t about creating users faster for its own sake. It was about understanding how the directory behaves at scale, how mistakes propagate, and how to recover cleanly when something goes wrong - where breaking things was not only acceptable, but the point.

What Comes Next

This Active Directory deployment is just the starting point. The real value of the lab is how it fits into a larger, evolving environment where services depend on one another and failures have downstream effects.

Over time, I plan to use this domain controller as the identity backbone for additional virtual machines and services, including:

- File servers with role-based access to departmental shares

- DNS and DHCP infrastructure tied into Active Directory

- Group-based access control to network resources

- Service accounts supporting applications and background jobs

With that foundation in place, I want to explore more operational scenarios that don’t show up in small or isolated labs:

- Monitoring directory health, replication, and authentication events

- Auditing access and understanding how group changes affect permissions

- Testing policy changes and observing unintended consequences

- Simulating account lifecycle events across multiple dependent systems

As the environment grows, so does the opportunity to practice thinking holistically - not just about individual services, but about how they interact, fail, and recover together.

More than anything, this lab gives me a space to learn deliberately. I can experiment, make mistakes, revisit design decisions, and refine them over time. Each iteration adds context that’s hard to get from documentation alone.

I plan to continue expanding this environment incrementally, documenting what works, what breaks, and what I learn along the way.